One of the more disturbing trends that we see in today’s society is the rise of anti-intellectualism. The bias against experts is not new, but it has grown exponentially during the pandemic years with the result of hundreds of thousands of needless deaths. Even now, the pandemic is continuing in the US despite the ready availability of vaccines largely because of a backlash against experts.

I remember one Twitter exchange that I had a while back in which another user wanted me to stipulate that the experts were always wrong. What? Of course, I won’t stipulate that because it’s an idiotic statement. If experts are always wrong, then they aren’t really experts, are they?

That isn’t to say that experts are always right, either. Experts are human and therefore fallible, but they do have a deeper knowledge on a given subject than a layman. That’s what makes them experts. It also makes what they have to say worth listening to, but it doesn’t mean that they shouldn’t be questioned.

In fact, one of the most useful techniques for determining truth is by questioning people and having them defend their ideas. This is especially true when experts have to defend their ideas to other experts. This peer-review process is part of the scientific method in which a hypothesis is tested and refined.

A lot of people assume that all experts are on the same page and in total agreement. That is rarely true. We can see from conflicting studies that each side cites in the pandemic that there are disagreements. Not all the data lines up in a nice, neat row.

And that’s one of the reasons for confusion. One study reaches one conclusion on a subject, masks for instance, while a different study reaches a different conclusion. People trying to make a point latch onto the study that reaches the conclusion that they want and discard contradictory information as “fake news.”

But that is not an honest way to do business. If you want to find the truth, rather than just hear a study that tickles your ears, you have to look at the big picture.

I’ve frequently written that you shouldn’t look at one poll in isolation. You should follow polling trends and look at the average of polls, discarding the outliers, to get a better sense of what is happening. It’s the same with scientific studies.

When considering the science of a subject, don’t stop at one study. Look for the preponderance of the data and discard the outliers. If a couple of studies say masks are useless but a lot of other studies say that they are effective, the odds are pretty good that they help. And that’s the reason why doctors have been wearing them for more than 100 years.

Most of us don’t have the time and many of us don’t have the background to parse all these data points. It’s easy to be overwhelmed and misled by technobabble if you aren’t well versed in the field. That’s where trusted experts come in handy.

And I do mean trusted. The problem that we have today is not that we don’t have enough information but that we have too much bad information. The internet has made it cheap and easy to broadcast to millions of people, even if you have absolutely no idea what you are talking about. A high school dropout broadcasting a rant from behind the wheel of his car can carry just as much weight among internet users as a scientist. Actually, the dropout probably carries more weight because he’s more entertaining.

Well-intentioned but uninformed people can misinterpret even good data. One common error is to focus on one aspect of a study without considering the larger context.

There’s also the fact that, as Mark Twain said, “A lie can travel around the world and back again while the truth is lacing up its boots.” That’s even more true today because a snappy soundbite or a sharply worded meme can spread like wildfire, regardless of whether it is true or not.

However, not all memes are bad. I happen to be a fan of the genre. Some, like the one below, make valid and truthful points in a memorable way.

People really should take a few minutes to look up information before believing it or passing it along. In another recent Twitter exchange, a user claimed that vaccinated individuals had turned out to be “superspreaders” in some areas.

“Name one,” I challenged, and she answered that Vermont had the highest vaccination rate and also the highest COVID numbers at the moment.

The key here is that we have two data points, but is there a causative relationship? I didn’t look to see whether Vermont had the highest vaccination rate, but I did determine that the state has about 80 percent of its population with at least one dose and 71 percent with two doses. Whether the state has the highest vaccination rate or not, that leaves about 20-30 percent of the population not completely vaccinated, which provides ample room for the virus to run amok.

But is that what happened? It took a little searching to find statistics on breakthrough infections, but the Vermont Department of Public Health does publish them. The most recent data set shows that breakthrough infections have affected only about 1.3 percent of Vermonters. (Of that number, only one percent have died and three percent were hospitalized.) That means the vaccines are tremendously effective but leaves the question of who is getting sick to bump the state’s case rate up so high.

That answer is also in the DPH report. Overall, 20-29 year-olds have had the highest rate of COVID-19 infections in Vermont, but the report shows that the current rate is highest among children 11 and younger. This is interesting because, up until last week, this age group was not approved for COVID vaccinations.

Huh. The unvaccinated are getting infected. Imagine that.

If you’ve stuck with me this long, you can see how the meme-style tweet was technically correct but fundamentally flawed in the information that it presented. Not many people are going to dig to resolve that sort of discrepancy, unfortunately. At first, digging up data can seem daunting, but it gets easier with practice. And a lot of the time, an internet search will show that someone has already done it for you.

And this sort of thing comes up a lot. A recent article that I wrote debunked similar claims about Israel that took highly specific data and tried to draw a general rule from it. The old saying that “figures lie and liars figure” is still true and when someone focuses on one small area to the exclusion of all else, it should be a red flag.

Oftentimes, the problem isn’t that the experts are wrong, it’s that we just don’t want to hear the message. You can attack people like Dr. Fauci and be tired of pandemic mitigations, but that won’t stop the relentless march of the virus across your community. Facts don’t care about your feelings.

And I’m not saying that Fauci is never wrong. As I said above, he’s human and he and the other medical experts were dealing with a completely new and unknown pathogen when it first hit the US back in the spring of 2020. They made some bad calls, such as when Fauci said in January 2020, “Even if there's a rare asymptomatic person that might transmit, an epidemic is not driven by asymptomatic carriers."

That line is an example of how people claim that Fauci and other experts lie. The problem is that it was not a lie at the time. It was historically true but was subsequently shown not to be true in the case of COVID-19 by new research. There’s that scientific method again.

The liars are the people who keep trotting out these debunked claims in order to undermine faith in institutions and science. These people are either ignorant of the facts or are maliciously deceiving their readers.

What should a savvy consumer of information do? Look for objective sources rather than partisan rage sites for one. Keep a mental note of a source’s track record on whether their predictions and claims come true for another. Read the fine print and look at the big picture.

Don’t believe the experts just because they are experts (or because they claim to be). But don’t disbelieve them because they have expertise in an area either. Do your homework with legitimate sources and find the objective truth.

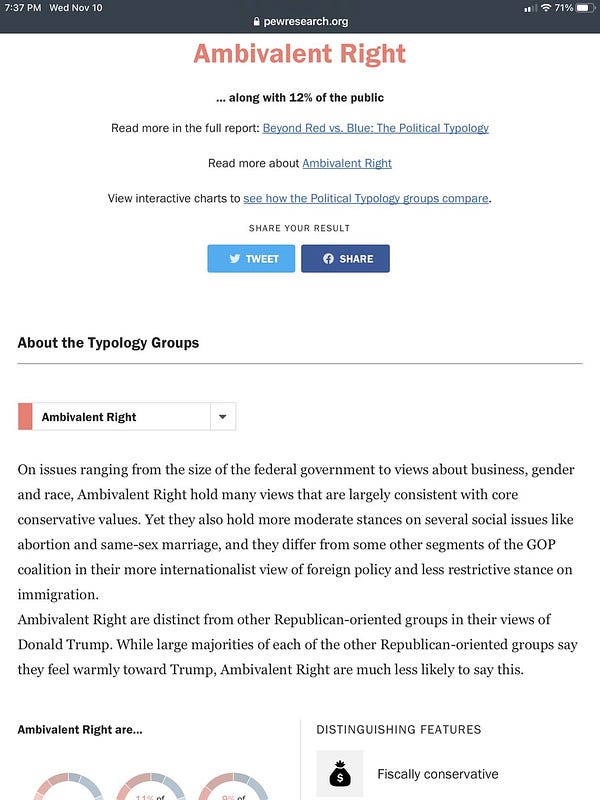

I’m sharing my conservative bona fides once again. A new political quiz has been going around and I came up as Ambivalent Right. If you’d like to take the quiz, you can do so here.

Joe Walsh @WalshFreedom

According to @pewresearch, my political group is Ambivalent Right, which includes 12% of U.S. adults. Take the Political Typology Quiz to see where you fit. https://t.co/BSc3u4FzdxHow do I feel about being part of the Ambivalent Right? Frankly, I’m ambivalent. It seems like a stupid label. It reminds me a lot of Futurama’s episode about the Neutral Planet, which is definitely worth watching if you haven’t seen it.

Unlike the Neutral leader, I do have strong feelings, but I’m definitely ambivalent about the options on the table.

No comments:

Post a Comment